Recently there have been several posts about what temperature it is safe to allow a tortoise outdoors, as we normally see this time of year. So instead of a reply to an individual post, I thought I would post a new thread that could be referred to and more could see.

My biggest concern with the question as temperatures cool "what temperature is safe for me to take my tortoise outdoors?" is that there is no single, simple answer. The air temperature is 3rd in my list of considerations for answering this question, yet most tend to only give answers based upon that factor alone. For a burrowing tortoise who naturally uses a burrow to moderate and control its temperature, the answer is even more critically controlled by these factors. Tortoises are designed to use the ground to moderate temperatures. With their flat plastrons lying against the ground and their organs positioned in their body towards the plastron to take advantage of this, ground temperature is a key to understand tortoise therm o-regulation. With a better understanding we can see how sulcatas, for example, can survive the extremes of the Sahel and indeed what temperatures they have evolved to live in. A basking tortoise resting on the ground is subject to solar radiation, which is greatly affected by the height of the sun above horizon as the atmosphere reflects and filters far more as the sun is lower and an extreme difference in that reflection happens as it get lower than about 45° altitude above horizon. Additionally, tortoises are quick to find places to hide and feel secure. However, they also evolved knowing these places are also protected from temperature extremes. But they come from areas where theses hiding spots are heated by much warmer deeper ground temperatures than we have in the US and Europe for most of us.

To me the answer must consider:

1 - the base ground temperature of that area of the world.

2 - the angle of the sun above horizon

3 - the air temperature

There are other consideration, of course, (wind, moisture level of the ground, etc) but these three will give a pretty safe answer.

1 - What I call the "base" ground temperature of a region. If we look at all the data collected by passive heating and cooling scientists, we see there is indeed a lot of data as they are designing systems to use the ground temperature to heat or cool a building to dramatically reduce the need for more energy dependent heating. Here are 2 charts we can refer to to discuss this:

This is a chart of the ground temperatures in the US. This is the very stable temperature that exists about 30 ft underground. This temperature corresponds to the average YEARLY air temperature of that particular area. That temperature varies throughout the year by only 1°-2°. It is also the temperature most folks in the water well industry know as the temperature the water will be pumped from an underground well. SO although we have a nice chart here for the US, we can easily determine a very close answer for an area elsewhere if we look at that area's average yearly air temperature.

Here is a chart the passive heating/cooling folks will use to consider when designing a system based upon the depth they will use for the air chamber they will draw from. So depending upon where you are, the scale on the top of the chart needs to be modified to match the yearly swing in average temperatures winter to summer. In the US that averages around 40°F. It shows the amount of swing in temperature you will see on a yearly basis at the various depths as we get less than 30 feet deep.

From this chart we can see as an example that a burrow (in our interest) that is 6 ft deep can swing as much as 10°F each side of average from summer to winter. A burrow in the shade of a bush will swing much less.

So if we apply this to the many question about why @Tom and I are always advising night box temperature for a sulcata above 80° we and now apply some data to see where this answer is based:

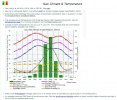

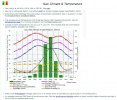

Let's look at one of the main remaining areas sulcatas are still found in fair abundance - Gao, Mali area. This is actually an area that gets a bit colder at night than much of the sulcata range, but still serves as a good basis:

We can see the average yearly air temperature for this area is actually 85.8 degrees. The yearly swing in temperatures for the area is about 22°F - so the scale on the variation chart would go from -11° to +11°. That burrow of a sulcata is normally 8-15 meters long. Almost always dug at an angle of 30°, a 10 meter (33ft) burrow will end up 16 feet deep. These are also most often dug into a slope of a hill so the actual depth is much more, but just using the 16 feet, we see the temperature over the course of a year at the bottom of that burrow will vary 2° on either side of average. SO the coldest we would expect that burrow is 83.8°F the coldest part of the year on the coldest night. Even though the temperature we see from the climate data above will drop to 14.6°C (58°F) in the burrow where the sulcata is it is a toasty 84°. And the next day above ground air temperatures will heat on average to 88° and sunny during that "coldest" part of their winter.

2 - angle of sun above horizon. In looking at the example above for a sulcata, we can also now add that mid January the sun there is still 51° above the horizon - plenty of solar intensity. The solar intensity of an area changes dramatically once the sun gets below 45° above horizon midday. I think a key reason why globally, we do not find tortoises occupying areas of the world above 50° latitude at the extreme (Russian tortoises). They have only about 4 month of the year there where the sun is high enough to really provide the intensity for proper heating.

So as an example, for our friends in the UK, a January day in Manchester will have the sun at 16° above horizon midday, while someone in Texas giving advice based upon their experience will have the January sun at 37° above horizon. A huge difference in solar intensity! A 65° day will be entirely different for a tortoise and its ability to absorb solar radiation for basking heat.

3 - It is only after considering these 2 factors above that air temperature is considered. And... it really isn't as much as a consideration as cloud cover.

So when we ask "What temperature is OK for my tortoise to be outside?" We need to consider a few of these things before giving an answer!

My biggest concern with the question as temperatures cool "what temperature is safe for me to take my tortoise outdoors?" is that there is no single, simple answer. The air temperature is 3rd in my list of considerations for answering this question, yet most tend to only give answers based upon that factor alone. For a burrowing tortoise who naturally uses a burrow to moderate and control its temperature, the answer is even more critically controlled by these factors. Tortoises are designed to use the ground to moderate temperatures. With their flat plastrons lying against the ground and their organs positioned in their body towards the plastron to take advantage of this, ground temperature is a key to understand tortoise therm o-regulation. With a better understanding we can see how sulcatas, for example, can survive the extremes of the Sahel and indeed what temperatures they have evolved to live in. A basking tortoise resting on the ground is subject to solar radiation, which is greatly affected by the height of the sun above horizon as the atmosphere reflects and filters far more as the sun is lower and an extreme difference in that reflection happens as it get lower than about 45° altitude above horizon. Additionally, tortoises are quick to find places to hide and feel secure. However, they also evolved knowing these places are also protected from temperature extremes. But they come from areas where theses hiding spots are heated by much warmer deeper ground temperatures than we have in the US and Europe for most of us.

To me the answer must consider:

1 - the base ground temperature of that area of the world.

2 - the angle of the sun above horizon

3 - the air temperature

There are other consideration, of course, (wind, moisture level of the ground, etc) but these three will give a pretty safe answer.

1 - What I call the "base" ground temperature of a region. If we look at all the data collected by passive heating and cooling scientists, we see there is indeed a lot of data as they are designing systems to use the ground temperature to heat or cool a building to dramatically reduce the need for more energy dependent heating. Here are 2 charts we can refer to to discuss this:

This is a chart of the ground temperatures in the US. This is the very stable temperature that exists about 30 ft underground. This temperature corresponds to the average YEARLY air temperature of that particular area. That temperature varies throughout the year by only 1°-2°. It is also the temperature most folks in the water well industry know as the temperature the water will be pumped from an underground well. SO although we have a nice chart here for the US, we can easily determine a very close answer for an area elsewhere if we look at that area's average yearly air temperature.

Here is a chart the passive heating/cooling folks will use to consider when designing a system based upon the depth they will use for the air chamber they will draw from. So depending upon where you are, the scale on the top of the chart needs to be modified to match the yearly swing in average temperatures winter to summer. In the US that averages around 40°F. It shows the amount of swing in temperature you will see on a yearly basis at the various depths as we get less than 30 feet deep.

From this chart we can see as an example that a burrow (in our interest) that is 6 ft deep can swing as much as 10°F each side of average from summer to winter. A burrow in the shade of a bush will swing much less.

So if we apply this to the many question about why @Tom and I are always advising night box temperature for a sulcata above 80° we and now apply some data to see where this answer is based:

Let's look at one of the main remaining areas sulcatas are still found in fair abundance - Gao, Mali area. This is actually an area that gets a bit colder at night than much of the sulcata range, but still serves as a good basis:

We can see the average yearly air temperature for this area is actually 85.8 degrees. The yearly swing in temperatures for the area is about 22°F - so the scale on the variation chart would go from -11° to +11°. That burrow of a sulcata is normally 8-15 meters long. Almost always dug at an angle of 30°, a 10 meter (33ft) burrow will end up 16 feet deep. These are also most often dug into a slope of a hill so the actual depth is much more, but just using the 16 feet, we see the temperature over the course of a year at the bottom of that burrow will vary 2° on either side of average. SO the coldest we would expect that burrow is 83.8°F the coldest part of the year on the coldest night. Even though the temperature we see from the climate data above will drop to 14.6°C (58°F) in the burrow where the sulcata is it is a toasty 84°. And the next day above ground air temperatures will heat on average to 88° and sunny during that "coldest" part of their winter.

2 - angle of sun above horizon. In looking at the example above for a sulcata, we can also now add that mid January the sun there is still 51° above the horizon - plenty of solar intensity. The solar intensity of an area changes dramatically once the sun gets below 45° above horizon midday. I think a key reason why globally, we do not find tortoises occupying areas of the world above 50° latitude at the extreme (Russian tortoises). They have only about 4 month of the year there where the sun is high enough to really provide the intensity for proper heating.

So as an example, for our friends in the UK, a January day in Manchester will have the sun at 16° above horizon midday, while someone in Texas giving advice based upon their experience will have the January sun at 37° above horizon. A huge difference in solar intensity! A 65° day will be entirely different for a tortoise and its ability to absorb solar radiation for basking heat.

3 - It is only after considering these 2 factors above that air temperature is considered. And... it really isn't as much as a consideration as cloud cover.

So when we ask "What temperature is OK for my tortoise to be outside?" We need to consider a few of these things before giving an answer!